The Event

The chain of circumstances that culminated in the loss of RMS TITANIC remain notable for the contradictions between industrial prowess and technical limitations: that ingenuity can be easily undone by complacency; that the most highly rated Ship Master of his day, Capt. Edward J. Smith, could make a series of disastrous judgments on a serene night; that while a sharp lookout is good, slowing down in the vicinity of icebergs is probably better; that although Marconi wireless was a dazzling invention of the age, mid-ocean ice warnings remain worthless if they never reach the officers in command; and that carrying enough lifeboats is essential, but filling the boats on board to capacity is urgent. The program will interpret these actions and inactions both as examples of human folly and as fundamental truths of human nature.

The Characters

Embed from Getty Images

Captain Smith (at Right)

Embed from Getty Images

TITANIC Crew

Presumed Iceberg that Sank TITANIC

as Seen from German Liner Prinz Adalbert

In an attempt to avoid hitting the iceberg, First Officer William Murdoch ordered an emergency turn to the left. This put the ship’s forward right flank in a vulnerable position, causing it to strike and scrape along the massive submerged base of the iceberg. Although described as a faint grinding jar, the hull was ripped open for about 300 feet, more than a third of her length.

Further maneuvering to escape the iceberg, the TITANIC managed to get her stern clear, and she slowed to a stop once beyond the iceberg. Initial reports of damage were incomplete, and the damage was not considered serious. Based on this incomplete information, the engines were restarted to half-speed ahead, but after a few minutes, they were stopped for good. Only when the damage was fully appreciated, did it become apparent that the ship was doomed—and with her, a majority of the persons on board.

Open ‘D’ Deck Gangway Door

Not well organized for such an emergency, the crew did what they could to get the boats loaded and away. The engineers stayed at their stations to keep steam up, lights on, and electricity supplied for the Marconi wireless. Although women and children were loaded into the boats first, this was not uniformly followed. Officers were wary of the strength of a fully loaded boat to sustain being lowered by rope tackles from the deck, and many boats left before being filled to capacity, with room for as many as 400 more persons. An ill-advised, deceptively safer alternative was to load passengers into the boats while they were floating alongside an open gangway door. However, this only accelerated the inflow of water into the ship. Nevertheless, and somewhat remarkably given the press of time, all the lifeboats were launched.

Eventually, TITANIC’s bow disappeared under the sea as the stern gradually rose, exposing the ship’s three propellers. The hull, unable to stand the great stress, began to buckle at the bottom with structural failure progressing to the superstructure. The sounds of the hull tearing itself apart were misidentified as the boilers tearing loose and falling forward. Finally, the hull failed completely. The bow headed to the sea floor, while the stern assumed the perpendicular, until it too finally disappeared under the sea.

Of those left in the water, only six were saved by the boats that floated nearby. As long as TITANIC’s lights were on, the boats “…were plainly visible, and they looked quite safe floating on the calm sea,” said 17-year-old Jack Thayer, who stayed with the ship nearly to the end. He somehow escaped the ship's suction and climbed onto an overturned lifeboat. Described as the buzzing of locusts, the torment of those in the water ceased and the sea became quiet once again.

Drawing by Ship’s Steward Leo J. Hyland

Rescue vs. Witness

Consider the contradictory actions of the nearest ships, Carpathia and Californian, one of which raced 58 miles through the same dangerous ice conditions in response to TITANIC’s distress signal, while the other stopped apparently in distant view of the unfolding disaster.

Aftermath

As the icy sea closed over the TITANIC, and those in the lifeboats grappled with shock and grief amidst the cries of the dying, it was already clear that significant changes would have to take place to prevent this from ever happening again. Additional life-saving equipment appeared to be the most immediate and obvious requirement. Further improvements would include a full-time wireless watch on all ships, where the wonderful Marconi instrument would be used diligently to receive ice messages; a reassessment of design and construction methods to improve vessel survivability in the event of damage; establishment of the International Ice Patrol; and moving transatlantic shipping lanes further south. All this, and more, came under the scrutiny of newly established international committees.

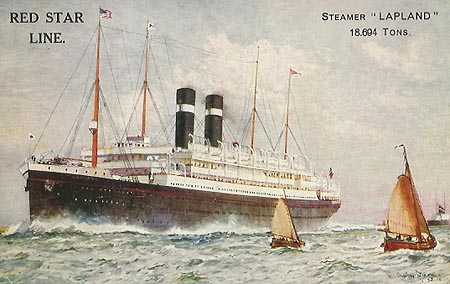

After surviving passengers and crew arrived in New York, they were housed in the Jane Hotel, across from Cunard Pier 54, where the rescue ship Carpathia docked. Surviving crew were told to say nothing about the sinking and were returned to England aboard the specially chartered Red Star Liner SS Lapland.

Embed from Getty Images

Crew Returns Home

The cable vessels Mackay Bennett and Minia, engaged as mortuary ships, had the grim work of recovering, identifying, and embalming bodies. Only about 10% of the 1,500 bodies lost with the ship were recovered: some children, some women, but mostly men. The last three male bodies were found adrift in one of TITANIC’s collapsible lifeboats. They were recovered about one month after the disaster by another White Star Liner, Oceanic.

Last Lifeboat Launched from the TITANIC

Embalming on the Cable Ship Minia

That summer, two inquiries were conducted, one by the United States, led by Senator William A. Smith, and the other by the British government, conducted by Lord Mersey. The hearing interviews concentrated on first-class passengers and crew, with fewer second- and only three steerage-class passengers interviewed.

The TITANIC was extolled as the next great accomplishment in British shipbuilding, British culture, and British influence. This compounded the loss of the great ship, and the news came as a cruel shock. The overwhelming loss of life among poorer passengers clashed with the idea of upper-class Anglo-Saxon male courage, which could not be reconciled with the fact that children traveling Third Class were more likely than men in First Class to perish. British Board of Trade life-saving regulations, hopelessly out of date, were immediately upgraded to require lifeboats for all. Some British crews on larger vessels refused to sail until their vessels were properly equipped.

With the loss of the TITANIC, Britain’s centuries-long supremacy in the world began its long decline; The sinking of the TITANIC was the overture, followed by overreach and unrest among Britain’s colonies, then by economic disasters brought about by two world wars. Nothing for Great Britain would ever again be the same.